America’s enemies learned from the Gulf and Iraq wars that they could not allow the U.S. and its allies geographic access to a combat zone, and have therefore developed denial techniques.

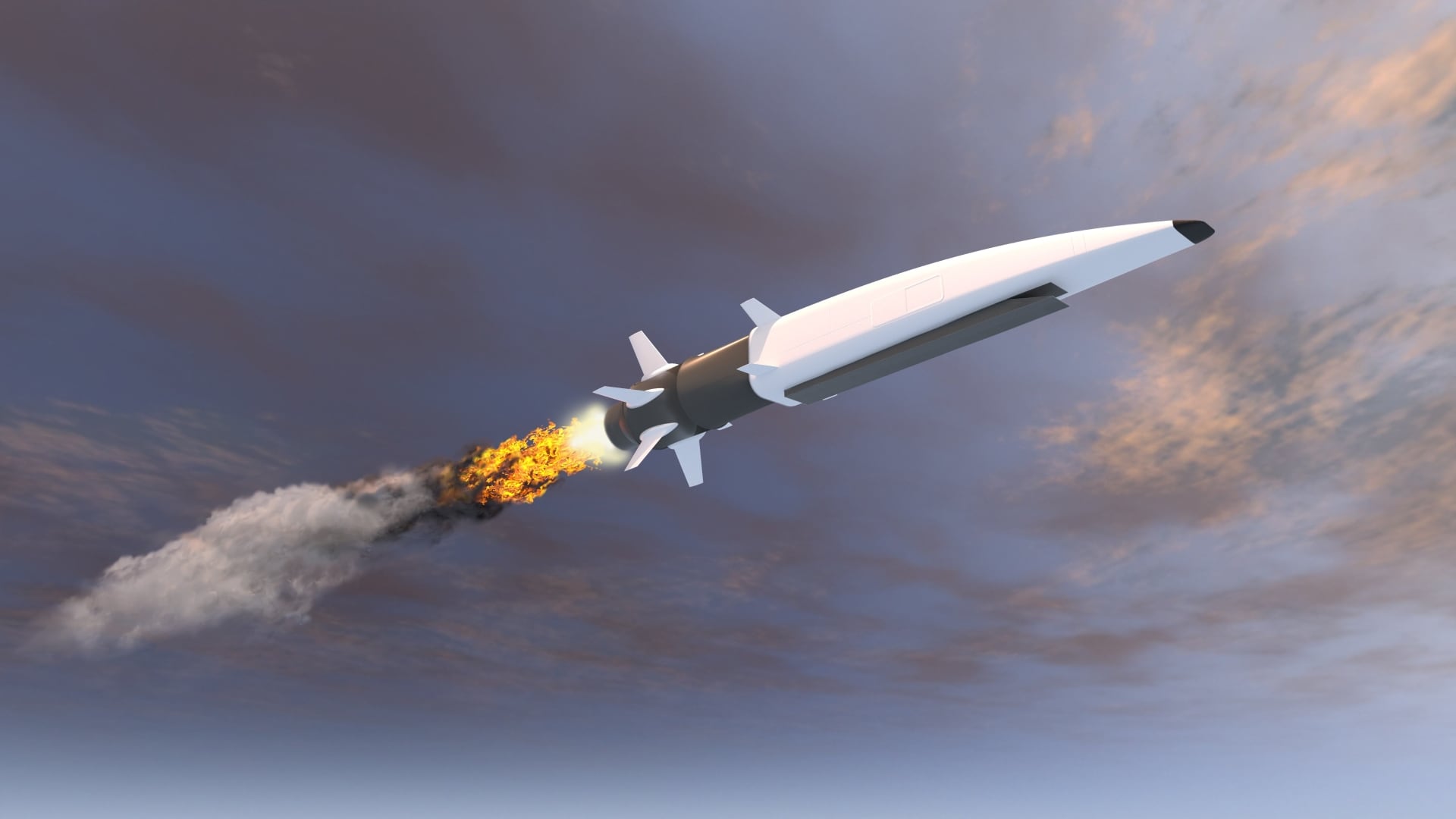

It is here that hypersonic weapons become extremely important.

Denying an enemy access to a combat zone requires enough long-range missiles to hold U.S. forces out of their missiles’ effective range. Two methods exist to execute this task: build enough missiles and launch platforms (ships, aircraft, submarines or ground-based launchers) to overwhelm an air defense system, or build munitions that can evade air defense systems.

Hypersonic weapons aid the latter aspect of this approach.

Both hypersonic cruise missiles and boost-glide vehicles travel six to 10 times faster and can maneuver far more effectively at high speeds than their non-hypersonic counterparts. This allows them to threaten theater-directed point or area air defense systems like those that currently defend U.S. carrier strike groups or major bases on Okinawa, Japan, or Guam.

By contrast, hypersonic weapons provide equivalent benefits to the United States. Countering Russian and Chinese objectives requires being able to penetrate their access denial networks. Stealth aircraft; low-cost, high-quantity warships; submarines; and unmanned systems will be critical in this mission. But hypersonics are equally necessary, considering the scale and sophistication of adversary air defenses.

If capable of being launched at range, hypersonics also allow the U.S. to leverage its most flexible military tool: the big-deck supercarrier’s combat air wing. A U.S. carrier group conceivably could remain beyond the range of all but a handful of Chinese missiles and conduct “standoff” strikes against enemy air defenses, supporting broader penetration efforts.

Of course, the more common public worry is that hypersonic glide vehicles on intercontinental ballistic missiles could transform the nuclear balance by obviating all air defense systems. But if hypersonic glide vehicles do obviate ballistic missile defenses, the standard logic of nuclear deterrence still applies.

To conduct a nuclear first strike, Russia or China would need enough missiles to cripple all land-based U.S. weapons and locate and destroy all U.S. ballistic missile submarines, or at least enough to mitigate retaliatory casualties to a still unacceptable 10-20 million. While possible, this would entail a massive expansion in both states’ nuclear arsenals. More reasonable is the proposition that China and Russia would use hypersonic-equipped ICBMs to raise the stakes of a response to regional aggression.

Would a president trade a U.S. population center to honor a commitment to the existence of an ally or critical partner? President Joe Biden, like all his predecessors, has provided no clear answer.

There is no weapon without a counter, either technologically, tactically, operationally or strategically. The Athenian Long Walls of Piraeus obviated Sparta’s original strategy during the Peloponnesian War. As a response, Sparta attacked Athenian allies, obtained a navy and gained command of the seas. Jacky Fisher’s brainchild, the HMS Dreadnought, outclassed every warship in the world when it entered service in 1906. But by 1916, Imperial Germany had built a dreadnought fleet large enough to challenge the British Royal Navy at Jutland. Additionally, the technological response to the dreadnought — the air- or sea-launched torpedo — was already under development.

Americans live not in an increasingly uncertain world, but an increasingly dangerous one. America’s adversaries, having prepared for competition over the last 30 years, are conducting a campaign to undermine its political position and, by extension, transform international society. Their sense of right is not ours, a fact that the genocide against Uighur Muslims or the attempted murder of Alexei Navalny demonstrates.

Of course, this nation cannot blindly trust new technologies to win its wars. It must do the hard work of strategic thinking and must turn to hardened practitioners — in other eras called statesmen — to defend its interests. It should avoid the temptation of technical flights of fancy and the sanctimony of scientific concern with equal care. Nevertheless, hypersonics deserve significant investment as offensive weapons, particularly at the theater level, as do missile defense technologies — if not for continental defense, then at least for tactical and operational purposes.

Seth Cropsey is a senior fellow and director of the Center for American Seapower at the Hudson Institute. He previously worked as an assistant to U.S. Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger and subsequently served as deputy undersecretary of the Navy in the Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations. Within the Office of the Secretary of Defense, he served as acting assistant secretary and then principal deputy assistant secretary of defense for special operations and low-intensity conflict. He also served in the Navy from 1985 to 2004.