For decades, the Pentagon, abetted by Congress, has behaved like a parent raiding a child’s college fund to pay monthly bills, rather than tightening its belt. Myopically robbing from critical long-term investments to pay for urgent needs resulted in the core problem addressed by the 2018 National Defense Strategy: America’s eroding military advantage against China and Russia.

The NDS, released under the leadership of Secretary of Defense James Mattis and Deputy Secretary Patrick Shanahan, strives to put a stop to this by emphasizing long-term competition with those major powers by prioritizing modern forces over larger, less capable forces.

But Shanahan’s response to news that the Department of Defense’s budget for fiscal 2020 would decline unexpectedly from a planned $733 billion to $700 billion — namely, that the smaller budget would rob funding from future modernization to build a bigger force for today’s problems — was enormously disheartening to those of us who helped create the strategy.

To be fair to Pentagon planners, a sudden drop in the budget this late in the process throw plans into disarray. However, the choice to prioritize near-term investments is flawed and unnecessary — even under a smaller budget. The NDS is a flexible strategy for 21st century great power competition. At its core is a prioritization framework that was designed to accommodate a broad range of uncertainty, including budget shifts.

Put bluntly, this shortfall shouldn’t invalidate the priorities of the NDS; rather, it should force the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the military services to prioritize more ruthlessly. Instead, it appears the OSD is abandoning the core principles of its strategy to fall back on the same approach that got us into our current predicament.

The NDS provides an excellent guide for ruthless prioritization. Investments should check our most capable competitors, lower the cost of long-term operations like counterterrorism and seize opportunities presented by rapid technological change.

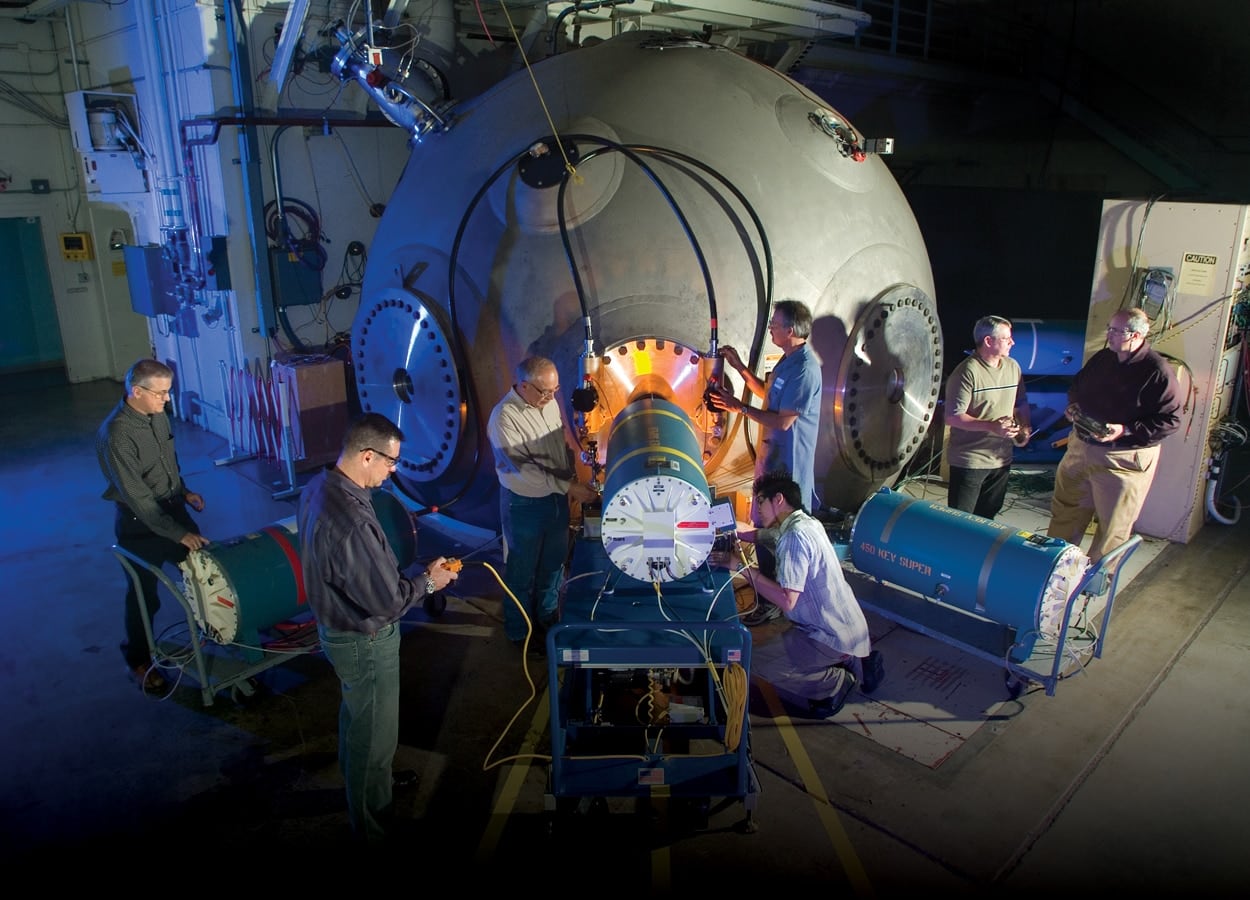

Senior Pentagon leaders and their staff are aware of the need to prioritize and, to the extent that a bureaucracy as large as the DoD can reach consensus, there’s broad agreement that the investments laid out in the NDS — such as updating nuclear capabilities; improved networks through space, cyberspace and the electromagnetic spectrum; and investments in artificial intelligence — are required for America’s future security.

So why the public statement to the contrary by Deputy Shanahan?

RELATED

It’s possible that the cuts to modernization are a negotiating tactic between DoD leadership and the White House, and particularly the Office of Management and Budget under budget hawk Mick Mulvaney. Withholding the important investments from the $700 billion budget will, the thinking goes, force the White House to increase the DoD’s top line in the president’s budget request.

But this approach is problematic for at least two reasons. First, it is unclear that this White House has a strong constituency arguing for advanced hardware. To the extent the president has commented on the military, he has usually argued for a larger force, e.g., more ships, a larger Army, more fighter squadrons, etc. Moreover, a larger military comprising big-ticket items like aircraft carriers and fighter aircraft engenders more political support than critical, but esoteric, investments in new networks or airbase resiliency. A budget that increases the size of the force at the cost of providing the U.S. military with better equipment for future wars may therefore be exactly what this White House wants.

Secondly, now that the midterm election has flipped the House of Representatives to the Democrats, this budget sends an enormously problematic message to a new leadership slate that is likely looking to trim the DoD’s budget. The $700 billion budget would tell them that there are savings to be had in deferring or halting the modernization of the force, but in reality nothing could be more costly to long-term national security.

Shanahan may just be doing the “logical” thing and going after the only pot of money available. Other accounts — such as force structure, O&M, and personnel — are structurally or politically difficult to access. And after five years spent digging out from the aftereffects of the sudden drop in readiness spending caused by sequestration, the DoD is loathe to touch that account.

But while bureaucratically and politically understandable, structural preferences for the present over the future have accelerated the erosion of our military advantage versus China and Russia. This problem isn’t new, but it is more urgent than at any time since the end of the Cold War. The future that once seemed distant is close at hand.

Mattis and Shanahan didn’t cause this problem, nor can they solve it with the FY20 budget. But they can at least break the myopic cycle by ruthlessly prioritizing per the NDS. Then, together with Congress, they can work to resolve some of the structural issues that plague the DoD’s translation of strategy into budgets.

Christopher M. Dougherty is a senior fellow on the defense team at the Center for a New American Security. He previously served in the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy (Strategy and Force Development) where he worked on the NDS Core Writing Team.