WASHINGTON ― As the U.S. Navy looks to fill capability gaps in its small surface combatants, the service is taking a hard look at international weapons and systems.

Two major programs ― the small surface combatant and the over-the-horizon missile for surface ships ― are seeing competition from international companies. As the Navy looks to replace its Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigates with a new guided-missile frigate under the FFG(X) program, several international designs have drawn attention inside the Navy.

The Italian FREMM, built by shipbuilder Fincantieri, is a serious contender for the Navy’s FFG(X), analysts and insiders say, and Kongsberg’s Fridtjof Nansen-class frigate ― a Norwegian design ― could also be drawing some attention. The Navy’s deadline for responses to its request for information released in July was Aug. 24, but details have not yet been released on who is in the game for the new ship class.

RELATED

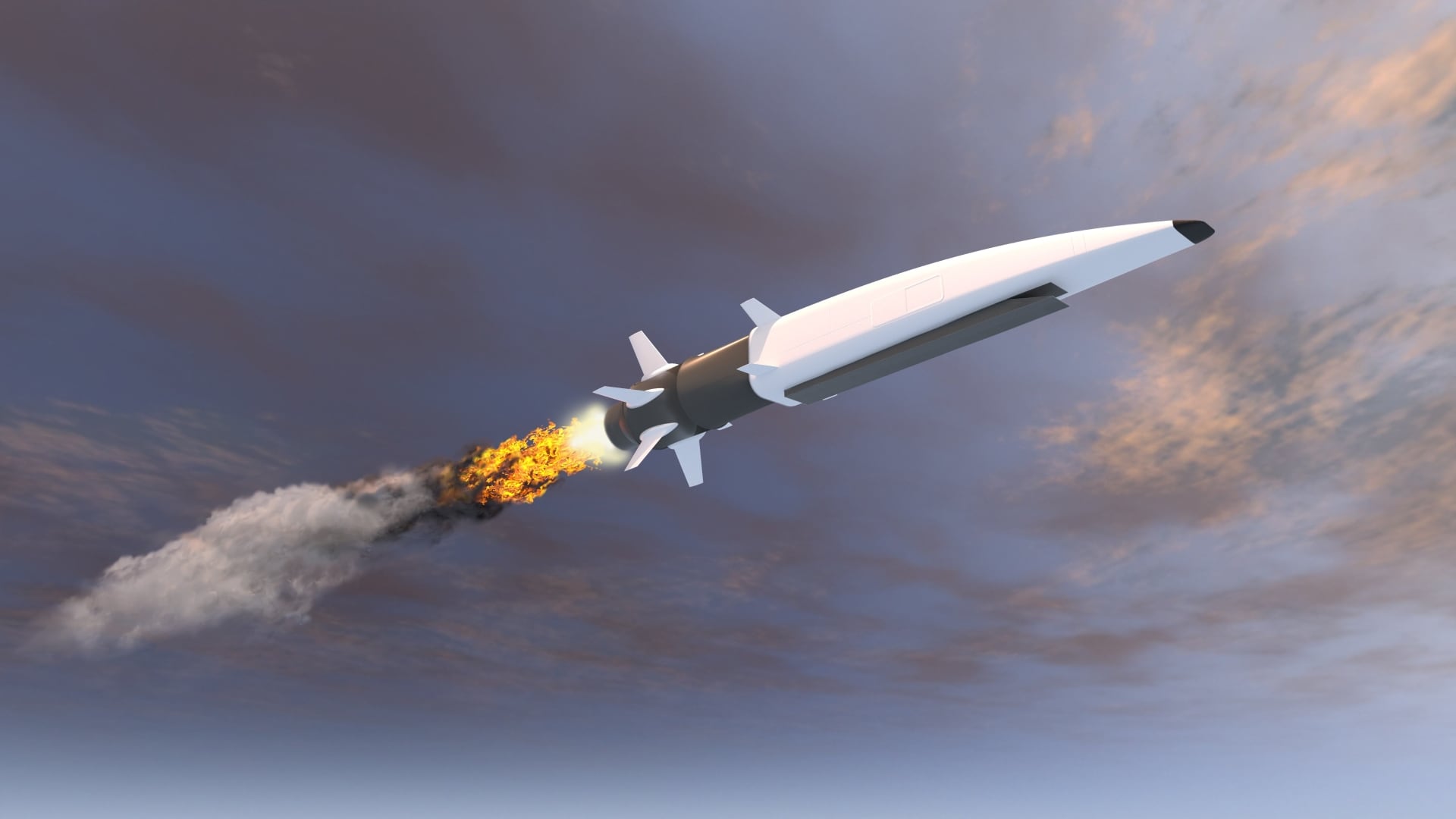

In the over-the-horizon missile competition, Kongsberg’s Naval Strike Missile is seen as the only serious contender after Lockheed Martin and Boeing both withdrew from the competition ahead of a June deadline for proposals. Kongsberg teamed up with Raytheon in 2015 to try and sell the missile to the U.S. Navy as it sought to make its surface combatants more lethal by giving it a longer-range, over-the-horizon, anti-surface missile.

The fleet’s mainstay anti-surface warfare missile for years was Boeing’s Harpoon missile, but as competitors began fielding longer-range, anti-surface missiles, the Navy was beginning to find itself out-sticked.

The Navy’s seemingly newfound openness to foreign designs, especially in the shipbuilding world, is likely a byproduct of the overall decline in U.S. shipbuilding, said Jerry Hendrix, a retired naval flight officer, historian and analyst with the Center for a New American Security.

“Because of the downsizing of the U.S. shipbuilding industry, you’re seeing more opportunities for foreign companies to invest in the U.S.,” Hendrix said. “And the downsizing is ossifying the design world as well to some degree.”

Both U.S. shipyards that are working on the littoral combat ship have foreign connections. The Marinette Marine in Wisconsin is owned by Fincantieri, and Austal USA in Mobile, Alabama, is owned by an Australian parent company. Both those yards have made significant investments in their facilities and processes that U.S. yards could learn from, Hendrix said.

“Foreign companies and foreign designs have some things to contribute to the U.S. shipbuilding industry,” he added.

Challenges

Sen. John McCain, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, has publicly encouraged the Navy to consider foreign designs in its frigate competition, arguing that the Navy needs to look to mature designs to get the frigate to the fleet faster.

“When you look at some of the renewed capabilities, naval capabilities, that both the Russians and the Chinese have, it requires more capable weapon systems,” McCain, R-Ariz., said in a speech in February.

In a hearing this May, the Navy said its goal was to get the first frigate in the water by 2024; the RFI for the FFG(X) program said the Navy was looking to start buying frigates in 2020.

But experts who spoke to Defense News on background said meeting that aggressive timeline with a foreign design, vice something like an adapted littoral combat ship, would be challenging.

Any foreign design would have to be, in essence, reverse engineered. Even the process of converting metric measurements in a foreign design to U.S. standard measurements is a time-consuming process. Then, once that process is complete, the ship would need to meet U.S. Navy survivability standards, which might entail significant design alterations.

In Congress, the idea of introducing foreign concepts triggers an automatic uneasiness, fearing that too much foreign influence could end up harming the domestic market and hurt U.S. jobs that depend on military spending.

But models such as Fincantieri’s partnership with Lockheed Martin to build the mono-hull version of the LCS, or Austal USA’s LCS line in Alabama, are models Congress is comfortable with, said Rep. Rob Wittman, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee’s Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee.

“It never hurts to look at what others are doing,” said Wittman, R-Va. “I think one of the key aspects of this is domestic shipbuilding capacity. We cannot drop below the level that we have and I think that is the key to this. … There are opportunities to look at partnering, like [Lockheed Martin] has done with Ficantieri for the LCS.”

When it comes to technology, however, Wittman said he’s eager to look at what other countries can add to the U.S. Navy’s arsenal.

“These countries are our allies, there is no reason why we can’t partner there,” Wittman said. “Most of the time the partnering is from the U.S. to those countries with the technology that we develop. I think technology transfers should be a two-way street. We shouldn’t be afraid to say: ‘Hey, maybe there are technologies and things like processes and design that we can learn from other countries and the things that they do with their ships.’ We should be able to bring that to bear in the United States.

“Still, there are two fundamental questions: We cannot drop below what is a critical industrial capacity in the United States to build our ships. But we should also look at what partnering opportunities are there with companies with that effort. We’ve done it with the LCS, it’s not a new thing. The question with the frigate is: Are there more opportunities out there like that?”

David B. Larter was the naval warfare reporter for Defense News.